When I joined Hornet, I had a lot of discussions with the team about how agents don’t search the same way people do. I wanted to see what that means for a “classic” keyword search stack, so we ran a small benchmark of BM25 + Block-Max WAND and looked at what happens as queries get longer and more complex.

When humans search, we usually prefer to type short queries. Just how short? The AOL search query log captures 36 million real queries from 650,000 users and remains one of the most comprehensive windows into human search behavior. Some key insights from the log include:

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean query length | 2.46 terms |

| Median query length | 2 terms |

| 90th percentile | 5 terms |

| 99th percentile | 8 terms |

Nearly two-thirds of all searches are two words or fewer. Fewer than one in three hundred queries exceed ten terms.

These characteristics shaped the last generation of search engine design. Now, search has a new user: agents. And agents don’t do two keyword queries, they generate long, structured queries. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. First, it helps to understand the fundamental innovations of search engines so we can see how they break in the agentic retrieval era.

Innovating search engines

Anyone can implement brute-force keyword search. Loop through every document in the collection, match the query terms against the document, compute a score based on the number of matching terms, keep a heap with the top-k scoring documents. It works, but computational complexity scales linearly with the number of documents.

Grow the number of documents by 10x, and the computational cost will grow by 10x. This type of search doesn't even require any index data structure. We can just scan through the data we want to search, similar to how grep works.

But linear brute-force search can’t handle corpora at the size of the web. If you try to grep over the entire internet you’re going to be waiting a very long time.

Query processing over inverted indexes

Keyword engines do better than grep by using an inverted index : for each term, store a sorted list of docIDs. When a query arrives, the engine looks up each term (typically in a trie or hash map) and retrieves the attached list of documents containing that term.

Disjunctive (“OR”) queries return documents that match any of the query terms, ranked by relevance score. When a user searches "expense policy reimbursement", we want documents containing "expense" OR "policy" OR "reimbursement", scored by how well they match.

Other boolean query types exist: conjunctive (“AND”) queries require all terms to match, phrase queries require terms in sequence, and hybrid queries combine these operators. Each has different performance characteristics, but disjunctive queries are the most common in text search applications.

Processing a disjunctive query means merging multiple posting lists (from the inverted index) and computing scores. A document matching all three terms scores higher than one matching just one. The naive approach iterates through all posting lists, accumulates scores for each document, and returns the top k.

This naive approach is effective but inefficient, especially as the number of terms increases. Dynamic pruning optimizations are therefore essential for search engines.

Dynamic pruning: the optimization that made search fast

Dynamic pruning algorithms have been the center of information retrieval research for decades. The goal: return the exact same top-k results as brute-force exhaustive search, but without scoring every document that matches at least one query term. That is, keep getting the best results without having to traverse every matching posting list.

The breakthrough came with WAND (Weak AND) by Broder et al. in 2003, building on MaxScore by Turtle and Flood from 1995. The key insight: if you track the maximum possible score contribution of each query term, you can skip documents that can't possibly make the top-k. In 2011, Ding and Suel introduced Block-Max WAND , which tracks maximum scores per block of the inverted index rather than globally. This tightens the bounds and enables even more aggressive skipping.

These algorithms power major search engine implementations today. Lucene adopted Block-Max WAND in version 8.0 (2019), bringing these optimizations to Elasticsearch, OpenSearch and Solr. For short queries, the reported savings are dramatic, often 10x or more compared to exhaustive scoring.

But there's an assumption baked into these algorithms: queries are short. These algorithms were tuned for a world where 90% of queries are four words or fewer.

Longer queries might break the optimization

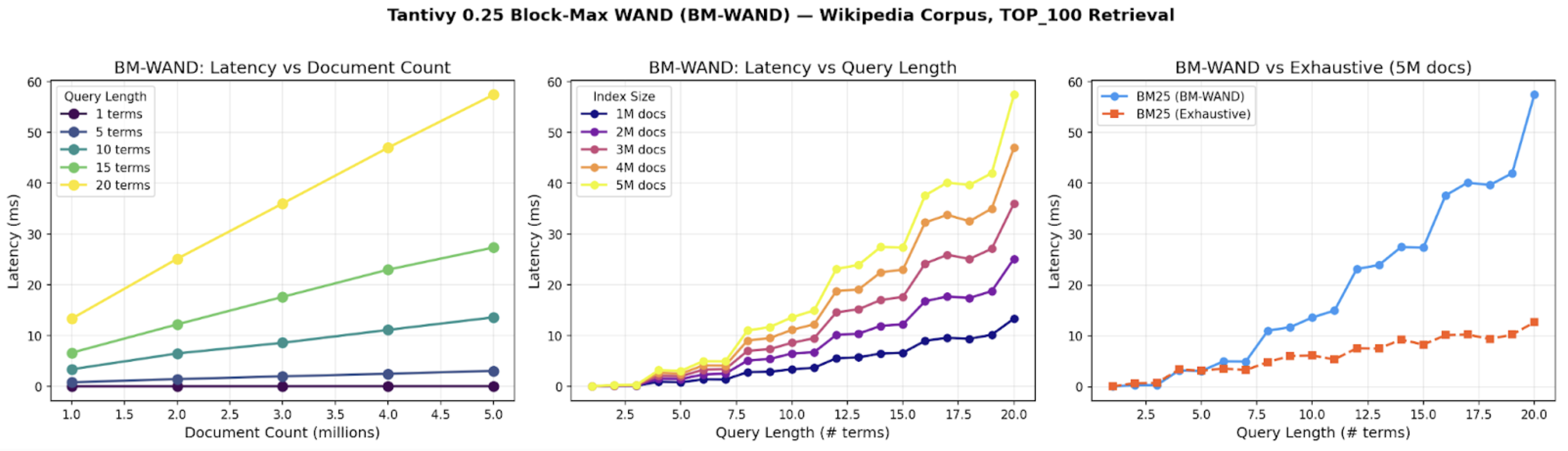

We ran benchmarks on Tantivy 0.25, a well-respected keyword search library written in Rust. Tantivy features SIMD-accelerated posting list operations and a solid Block-Max WAND implementation for top-k retrieval using BM25 scoring by default. Using Wikipedia articles from the search-benchmark-game corpus, we varied both document count (1M to 5M) and query length (1 to 20 terms). Queries were constructed by randomly sampling terms from the index vocabulary

For short queries (1-5 terms), BM-WAND works great as expected. Latency stays low even as the index grows from 1M to 5M documents. This demonstrates sub-linear scaling, which is an excellent property. We can double the index size while keeping latency almost the same, without adding any hardware.

For longer queries, we see that the slope increases with the number of query terms and the longer the queries are, the more costly the search becomes.

At about 7.5 query terms for the 5M document index, BM-WAND becomes slower than exhaustive search. See the right-most chart: BM-WAND latency crosses the exhaustive line beyond 7 terms. At 20 terms on a 5M document index, BM-WAND takes roughly 58ms per query. The same query using exhaustive scoring (without pruning) is actually much faster, taking only 12ms.

What happened? With many query terms, most documents in the corpus match at least one term. The pruning condition becomes harder to satisfy and therefore fewer documents are skipped. The algorithm spends more time maintaining its data structures than it saves by skipping documents.

But wait: random queries are not representative

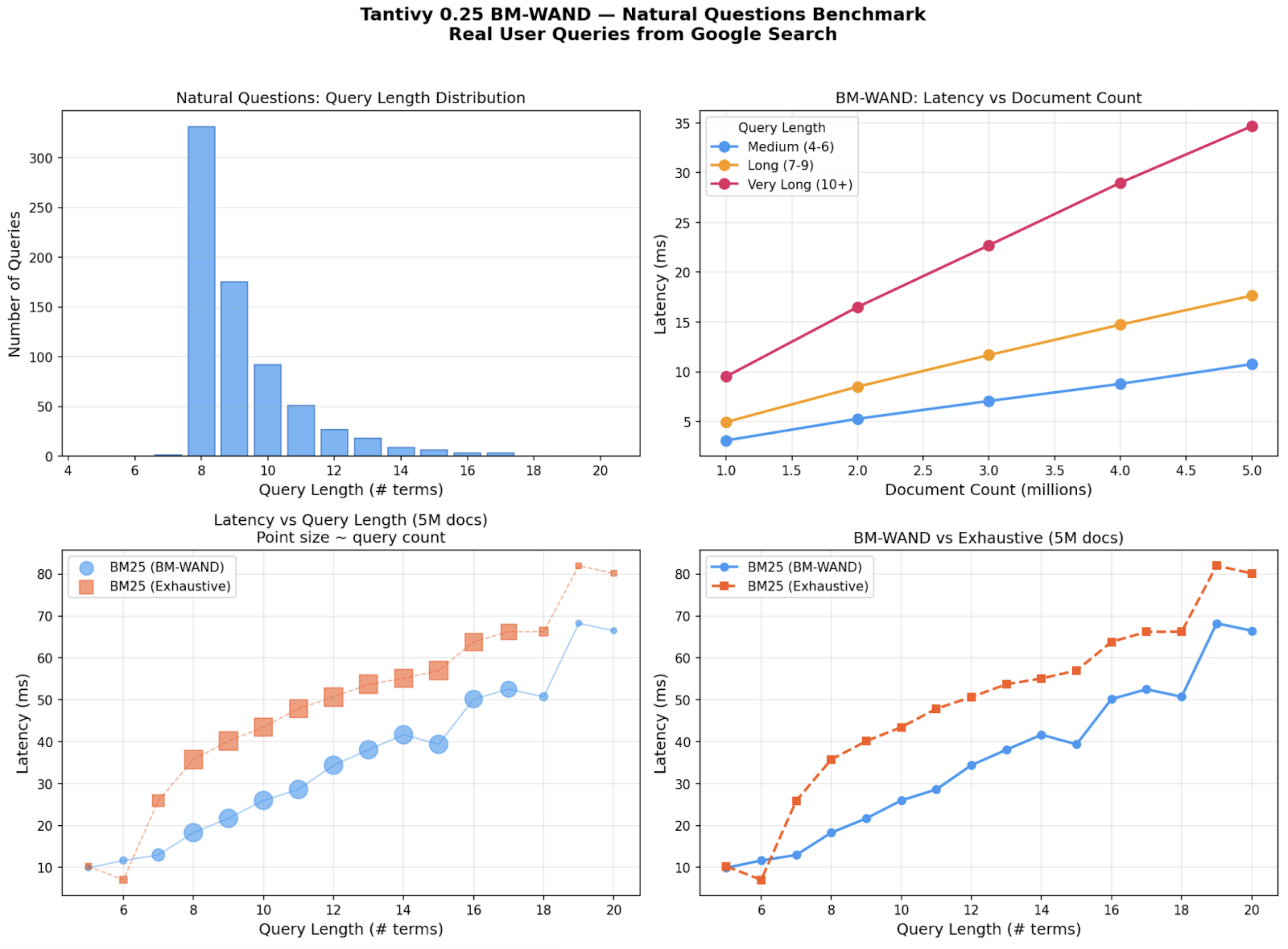

In the previous benchmark we used random sampling of keywords from the vocabulary to create queries of a specific length. We ran a second benchmark using Google's Natural Questions dataset: 3,610 real user queries with an average length of 9 terms. This dataset is a good proxy for agent queries because the questions are complete, natural language sentences rather than keyword fragments. They represent how humans phrase questions when they expect a direct answer, which mirrors how agents construct retrieval queries.

The results are different. With real human queries, BM-WAND performs better than exhaustive search by 1.5-2x across all query lengths. At 8 terms (the most common NQ length), BM-WAND takes 18ms versus 36ms for exhaustive search. The bottom-left chart above shows BM-WAND remains faster than exhaustive across most real query lengths.

Both BM-WAND and exhaustive search show a clear correlation between query length and latency. Longer queries cost more, regardless of the algorithm. BM-WAND at 15 terms takes roughly 3x longer than at 5 terms. The pruning optimization helps, but it doesn't eliminate the fundamental relationship: more query terms means more work.

What explains the difference compared to random queries? Query term weight distribution.

Real queries have uneven term weights. Consider "Who plays the mother in how I met your mother". Words like "who", "the", and "in" are extremely common and contribute almost nothing to the score (low IDF). The discriminating terms, "plays", "mother", and the show title, carry most of the weight. BM-WAND can more quickly establish a high score threshold using these few high-weight terms and skip documents that only match the low-weight stopwords.

Synthetic random-term queries defeat this mechanism. When we select random terms from the vocabulary, there's no small set of discriminating terms that establishes a high threshold early. The algorithm must evaluate more documents before it can confidently skip.

Latency is a proxy for cost

60ms per query doesn't sound like much. It's less than a blink of an eye. A human wouldn't notice. So what's the problem?

The problem is that latency here is a proxy for computational cost. A 60ms query consumes nearly 5x more CPU cycles than a 12ms query. When you're running thousands of agent queries per minute, that difference shows up directly in your infrastructure bill.

A query that takes 5x longer costs 5x more to serve. At scale, choosing the wrong algorithm is a cost multiplier. As we can also observe from the benchmarks, latency (and cost) for queries with many terms scales with both number of documents and number of terms.

Why this matters for agents

Remember the AOL statistics: 90% of human queries are four words or fewer. Agents flip this distribution on its head.

Query length. The median human query is 2 terms. Agent queries routinely hit 8-15 terms, putting them in the 99th percentile of human query length.

Query volume. A human analyst issues dozens of queries per session. An autonomous agent testing hypotheses might issue thousands in rapid succession, a 100x difference, compounding with query complexity.

The infrastructure assumptions of the human-search era, tuned for 2-term queries at human pace, are becoming obsolete in the agent-search era.

The agentic infrastructure shift

In our previous writing , we argued that agent-driven workloads change the shape of demand on infrastructure. The benchmarks shared in this post add nuance to that argument.

It's not that dynamic pruning algorithms are broken for agentic queries. It's that the algorithms need to adapt to query characteristics that vary more than they did in the human-search era.

At Hornet, we're building retrieval infrastructure that recognizes this distinction. Query execution that adapts to workload characteristics. Scoring strategies selected based on query structure. Systems designed for the volume, complexity, and variability of agentic workloads.

Agents are querying differently. Infrastructure needs to adapt or die.

If your query mix is getting longer and noisier, you’re not alone. We’re sharing what we’ve learned building the agentic retrieval engine. To be notified about new posts, benchmarks, and early product notes,